Heading East

When the Russian government introduced several programs to attract people to the Far East, many accepted the invitation. But what does it take to become a modern day pioneer? We talked to participants about their struggles, strengths and hopes.

Anna and Artyom Yevdokimovy and their two children spent seven days on the train, followed by a two-hour journey by car, to reach a tiny village called Romny in Amur Oblast, a region of the Russian Far East.

“The first thing you see when you arrive here is the Soviet infrastructure. Everything here reminds you of the Soviet Union,” Artyom says.

The Yevdokimovy are from Avdiivka, a city in Donetsk region of the Eastern Ukraine. Avdiivka was the site of some of the most brutal battles during the 2014 conflict between Ukrainian armed forces and pro-Russian separatists.

The family was seriously affected by the war: first, the Yevdokimovy had to send their children off to their aunt in Russia, then an explosion destroyed their apartment in Avdiivka and Artyom joined the pro-Russian side.

When the second Minsk Protocol was signed in February 2015, Artyom and Anna fled Avdiivka and moved to their Russian relatives to rejoin with their kids and to figure out the future. Soon they learned about a state program aimed at assisting the voluntary resettlement of compatriots – people who are fluent in Russian and accustomed to Russian traditions residing outside of the Russian Federation – and the Yevdokimovy decided to take a chance. They arrived in Romny in late summer 2015.

“We had only two backpacks,” Artyom says.

“We didn’t have lots of money, and our first salary would be only in a month since we just got the jobs,” his wife Anna adds. “We didn’t bring any warm clothes with us. We didn’t think that the winter would start early here. And – bang! [When we arrived], it was only plus 12 degrees [Celcius].”

The reasons

The Russian Far Eastern Federal District covers a third of the country’s territory, and more than half of this vast land is forest. It is a land of fascinating culture, picturesque views over the Pacific Ocean and the richest reserves of natural and mineral resources, yet only about 5% of the Russian population calls this place home, around 8 million people.

After the USSR collapsed and the remaining movement restriction laws fell apart, the population here started to decline rapidly. Between 1991 and 2016, almost two million people relocated to the central part of the country from its far eastern territories and, as some experts say, the region is still “a population donor for the rest of the country.”

Trying to prevent the population decline of the Russian Far Eastern Federal District, the federal government has introduced several programs that incentivize current citizens to stay and others to settle in the Far East.

The recent recipients of such government support spoke to us about their experiences, challenges and obstacles they have faced. It turns out that without the enthusiasm, strengths and faiths of the participants, these programs would have had little chance of success.

The Compatriots

The resettlement program was introduced in 2006 and has since gone through several revisions. For example, over time, the 11 administrative subdivisions of the Far Eastern region became prioritized by the program, meaning that if returnees choose this district over the others, they may count on more benefits.

Artyom said that they chose this region because they were promised to get their Russian passports quicker and they did, in fact, receive them in 2016.

The family had other options for resettlement destinations, including Australia and Israel, but they moved to this remote village in the Russian Far East hoping that it would be easier to blend into its small community – the population of Romny is about 3,000 people.

In their phone conversations with Romny’s authorities and their future employers, the Yevdokimovy were promised an apartment and jobs in the education and cultural sectors. All benefits would be effective upon their arrival. However, when they got there, no one met them, and they later learned that the apartment was not ready either.

In a great rush, the authorities found and rented out the first available one-bedroom apartment. It should have been bought by the municipal government later, but the officials forgot about the promise.

“We wrote everywhere, to any possible organization [asking to sort this problem out], but at the same time, there was a conflict at work and it felt like the community was pushing us away,” Anna said.

The Yevdokimovy decided not to wait for the government’s help. They took out a mortgage and bought the flat.

The Russian Far Eastern territories have undergone multiple development programs since the 17th century.

Three hundred years later, the region is still a national priority. Up to 2024, more than 2 trillion roubles [$25,000,000,000] will be spent on the national Far East development program.

The Hectare Owners

The Far Eastern Hectare [Dalnevostochny hectare] program is another attempt to stop people from leaving. It offers people land across the region for free. The program’s ambitious aim was to attract up to 30 million people, as well as to develop 170 million hectares.

According to the program’s website “To the Far East,” the application process is simple.

First, a person chooses a tempting piece of land online, develops an idea for its development, submits an application, and waits for the official confirmation, after which he can start working on the land.

The government follows up on the progress the owner has made within three years. If it is substantial – for example, if one wants to build a café and has started putting up a building within three years – the applicant can either buy the land or start renting it for the next 49 years.

The citizens of the Far Eastern region were the first ones to get a chance to apply and receive a hectare of land. As of February 2017 the program is open to all Russians.

Up to now, only 87,000 people have stepped up to take up the offer. According to official data, about half of them are planning to build a house on their land, others want to use the land for agricultural business or tourism purposes.

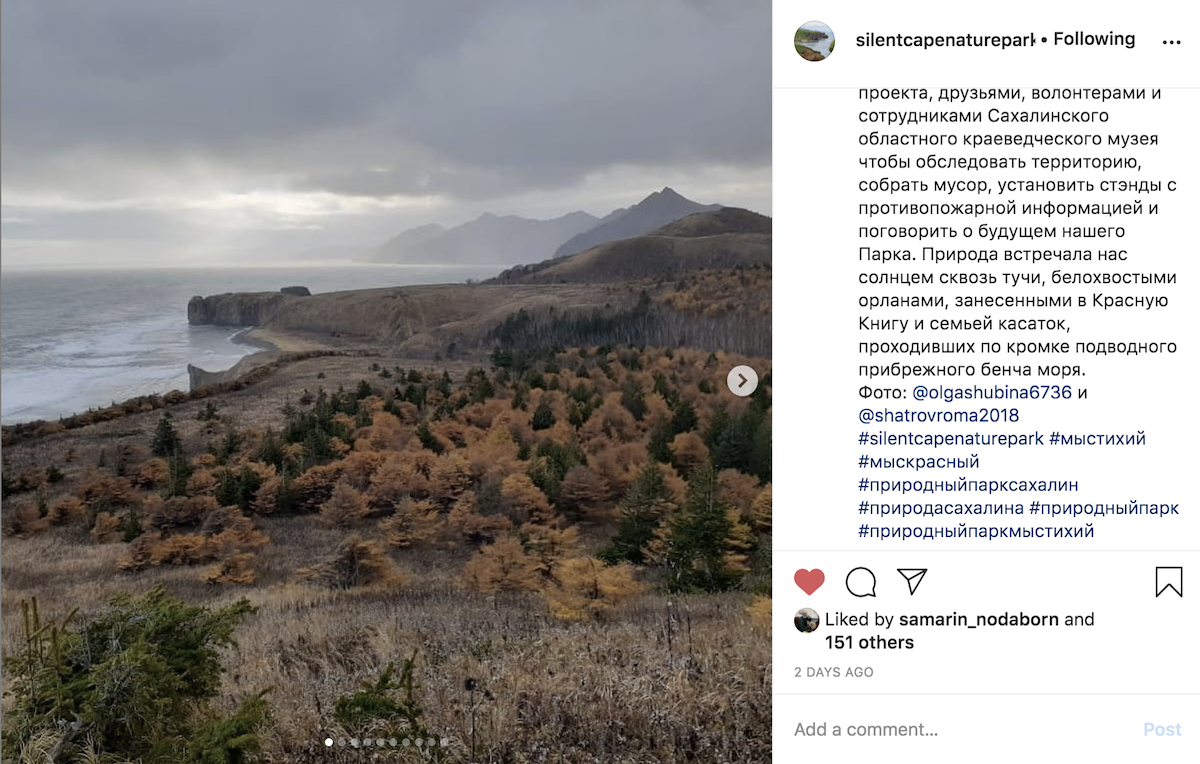

Roman Shatrov, a Sakhalin-based entrepreneur and environmental enthusiast, was one of the first to receive land on his native island.

He had an original idea of what to do with this land. When he learned about the state program, he decided to create a nature park and save the wilderness from any kind of intrusion. He turned to several friends and colleagues for help, and together they took 29 hectares and formed the first Russian community natural park called “The Silent Cape Nature Park.”

The park is located 130 km from the region’s capital, Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk. There is no direct road to the park. Its visitors have to drive to the closest point, then leave the car and walk about one kilometer.

Building the park is a very meditative process, Roman says. His team works here whenever they can. Some of Roman’s colleagues live in Moscow, but in 2019, Roman spent the entire summer here, running volunteer programs, cleaning and organizing a campground and recreational areas.

For Roman, the most challenging aspect of this project was putting together the documents needed to register any activities of the land due to the lack of guidance from the local authorities.

“Since our hectares are part of the state’s forest fund, any little development has to be reported. Each time we want to build in a tiny peg, we need to write a development project to the Ministry. The project is a 50-page document written according to the latest standards and full of complex tables. I asked officials for the templates, but was told that they didn’t have any… I almost got a second degree while studying on my own how these projects are supposed to be written. I have already written five of them,” Roman said.

Up to now, everything that they built in the park has been privately financed.

“We have no need to apply for state grants yet. These grants require strict accountability and great control. We don’t know whether we are ready for that yet. Right now, we are a group of citizens, but as soon as we become a union, we will receive a lot of attention,” Roman said.

Is It Working?

The “To the Far East” website claims that the hectare owners have received almost one billion roubles [$113,000,000] over the past four years. These were used as subsidies for livestock as well as microloans.

Mikhail Utrobin – an entrepreneur from Khabarovsk Krai and one of the program’s biggest success stories – became a participant in 2016 and received a state grant that covers expenses for his agricultural business. Mikhail is running a dairy farm and claims to have recently reached “financial stability.”

Even though his story seems hassle-free, Mikhail said he overcame numerous complications while building the house and the farm, and had to deal with misunderstandings with his employees and financial loss.

After surviving the four-year ordeal, Mikhail now proudly calls himself a pioneer and is advising other hectare-seekers.

“I think of it as a job, and like at any other job, I deal with different obstacles, but the most important thing is how you react to them. You might say that it’s too hard, you’re an unlucky person and the government forces you to do such and such… or you could say, damn it, I will do whatever it takes to reach my goals because I need to do that for myself, for my children and my family, and I don’t care about the difficulties. I will solve these difficulties at any cost,” Mikhail said.

Now Mikhail is fighting to get a Far Eastern mortgage with a subsidised rate of 2% (relatively small compared to the regular rate of 8%-9%). He has met all the criteria, but it has been a year since he applied, and he has not received any response yet.

“The program is not working yet,” he said.

However, with his pioneer approach in mind, Mikhail is confident that his mortgage application will eventually get through and, if the mortgage offer is functional, it will attract more people to the program.

“It is an ideal situation when land and [financial] resources are available. But when there is land and no money, the land is a dead weight,” Mikhail added.

Many of the offered lands are in the middle of nowhere with no basic infrastructure.

It Is Shaking up the Whole System, as if Hitting It with a Mallet

Utrobin’s farm is located close to Khabarovsk, one of the major cities in the Far East. The area around his farm is growing. Many people are taking land and starting to work there. Mikhail and his neighbours currently have one of the biggest properties. The local authorities have taken notice of them and are ready to build the extra electricity network and road that they need.

In 2018, another hectare-owners collective was registered as a village, and this year, officials mentioned that up to 100% of the expenses for building the village infrastructure might be covered by the federal budget.

In her research “‘Far Eastern hectare’: experiment of the creation of property right over land?”, Natalya Ryzhyova, a Russian researcher and economist, poses a question about the settlements and villages that were formed in the past and which are now slowly dying:

“Why is it necessary to develop something outside when there are so many already existing places (with infrastructure)? Who and at what expense will build new roads and other communications to these new lands? Why there, why not us?”

Due to the agricultural resettlement that took place on a large scale in the 1930s and again in the 1950s and 1980s, many villages and cities have popped up across the Far Eastern region. When people started to relocate to the west, many of them were abandoned or now have a rapidly shrinking population.

For example, Romny, where Anna and Artyom Yevdokimov have settled, used to have three major plants, which went bankrupt in the 90s.

“It’s a beautiful place. What if someone would try to revive it? If there were suitable jobs available, I would strongly encourage people to move here,” Anna said.

Anna has two jobs. She is an extracurricular teacher and music teacher in two schools. Her husband, Artyom, works at the largest supplier of petroleum products in the Amur Region. During his spare time, he runs the Amur regional children’s and youth Cossack organization.

The Yevdokimovy have had mixed experiences since coming to Romny, but they are not planning to leave. Even though she does not feel at home yet, Anna said she is grateful for the people around, who helped her family through the hard times.

Artyom and Anna are also running a WhatsApp group that offers advice to newcomers or people who wish to resettle to the region. The chat now has 45 participants (about 10 of which are local experts in migration law, translation, etc.).

Artyom said there could be more people interested in the program if they were sure they would get the support that they need.

Artyom and Anna dream of organizing a resettlement center in Romny where people could get some rest, stay while looking for apartments and have an opportunity to learn about their new home.

“Most of them [potential returnees] are held back by the uncertainty. They do not quite understand the whole process that they will have to go through, and they are afraid that they will not have time to find work, etc. It is important to have a center like this. It will address most of these concerns and give some guarantees to the person [potential returnee]. Then you can count on their interest growing,” Artyom said.

Artyom added that they do not have private resources to open such a place, so he is constantly looking for a government body that would support it.

“They [the government] said: ‘Start it and then we will back you up later’,” he said.

In two years, Roman Shatrov and his colleagues will apply for the right to rent their territory for the next 49 years. Since their land is part of the state forest fund, which cannot be sold, renting is the only available option. They cannot be registered as a community or private natural park since there is no applicable law in the Russian legislation.

Despite these difficulties, Roman remains hopeful that once the shortcomings of the program are ironed out, it will change the way people and the government collaborate, and what the Far East region will look like in the future.

“I think the program is fantastic. It’s timely, and it shows us the problems in how the officials currently work, the gaps that we have in the legislation, the huge number of requirements that contradict each other. This program is shaking up the whole system, as if hitting it with a mallet, and things are finally starting to change,” Roman said.