What's left?

Central Europe seems polarized: traditional parties cling to the status quo while right-wing populists push isolationist, xenophobic ideas. But on the Iberian Peninsula, things have taken a different turn – a turn to the left.

It’s only when I try to explain the landscape of Germany’s left to a young Portuguese woman, that I realize the disastrous shape we’re in. In Lisbon, smoking cigarettes on the street and looking down towards the moonlit Tagus River, I tell Alexandra Vidal about the left-leaning parties in the German election this year: the Greens Party seems to have forgotten its radical roots and is ready to form a coalition with the conservatives; the Social Democratic Party is courting the working class again after years supporting deep social cuts; and “The Left” is now dusty, torn up and desperately fighting irrelevancy.

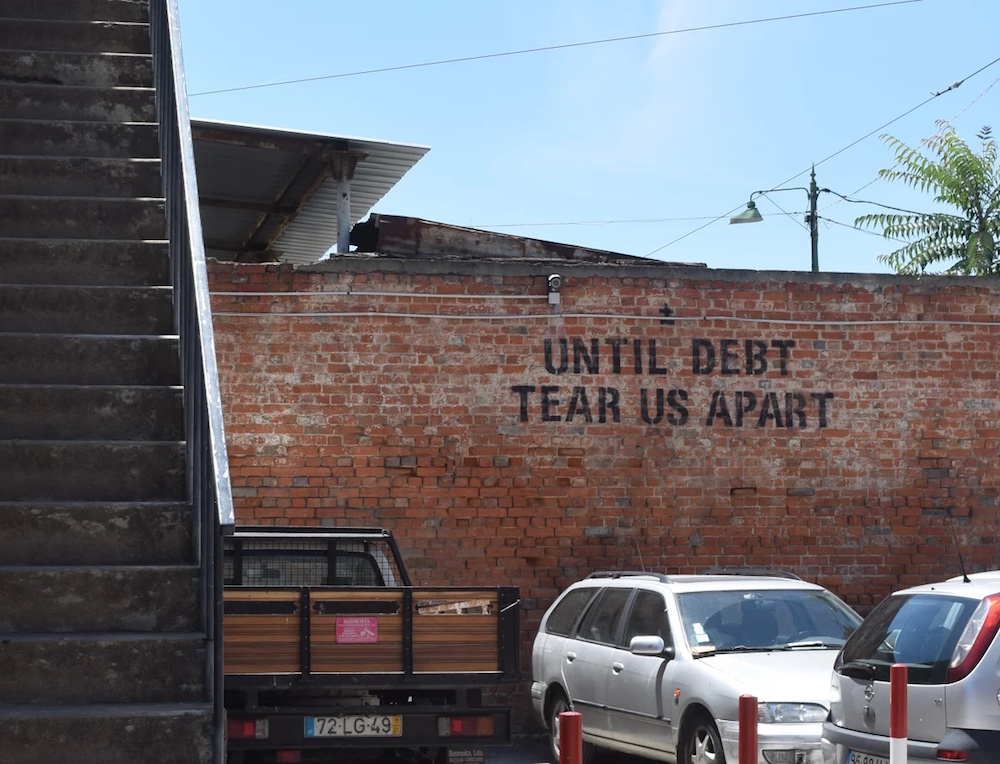

I explain that ‘leftism’ in Germany means rioting, Euroscepticism, or nostalgia for East Germany. I tell her that a German sociologist recently declared that left thinking is no longer needed– despite thousands of people drowning in the Mediterranean Sea each month, despite Europe being threatened by right-wing populists appealing to the forgotten lower classes, despite an increasing gap between rich and poor.

I tell her my fear that young Germans now consider preserving the status quo against the right-wing movement is a progressive stance. I tell her that in recent months, I’ve seen Germans wave European flags on public squares while blasting a heartbeat through their sound systems, symbolling a ‘Pulse of Europe’ that reverberates through the EU. It’s then that Vidal begins to laugh. She tells me she has definitely never heard that pulse.

We’re sitting next to Vidal’s alternative concert bar called Damas. After I’ve finished my lecture on German politics, she asks why I came to Lisbon.

Since 2015, Portugal has had a new left government. It’s a minority government lead by the Socialists and tolerated by a Greens-Communist alliance and Bloco Esquerda (‘Left Block’), a party founded in 1999 and lead by four young women. The government has turned away from austerity by raising public wages, getting investors into the country, financing start-ups and tackling unemployment. And even though the new political constellation was first called geringonça, which means something like “improvised contraption,” the government has proved stable. International media is talking about a boom in the economy and calling Lisbon the new “capital of cool.”

Similar things are happening in Spain where Podemos, a party that emerged from the anti-austerity movement 15M, has become the biggest party in the country. Other successors of 15M have taken over city councils in Madrid and Barcelona and are reshaping the cities through grass-roots democracy.

And so I tell Alexandra that I want to know whether talk of a ‘new left’ gaining ground on the Iberian Peninsula is true. I also want to know if “no” to austerity also means “no” to Europe.

Outside a train station in north Lisbon, surrounded by noisy traffic and a cold Atlantic breeze, Bloco Esquerda is presenting its candidates for the upcoming municipal elections.

Around 20 people, on average around 35 years old, sit on plastic chairs crowded around the party’s banner. They’re straining to hear the speeches above the background noise but they clap whenever necessary. Twenty-nine year old Ricardo Rivera is head of Bloco Esquerda’s student organization. He sits front row, filming his colleagues’ speeches with his iPhone.

“We want to be a ‘new left’ in a European sense,” Rivera tells me, after the last candidate has finished his speech. By “new,” Rivera means the party doesn’t shy away from issues the traditional communist party ignores, such as LGBT rights, environmental issues and women’s rights.

I wonder if Bloco Esquerda is merely a left-ish party that just aims to do no harm. “Of course not,” says Rivera. When the European Troika came to the country in 2011, Bloco Esquerda rejected any form of communication with them – a decision that lost them votes when pro-Troika conservatives won the next election.

“We completely misinterpreted the mood in Portugal back then,” explains Ricardo Robles, a Bloco Esquerda candidate, who has joined us to check out Rivera’s video of his speech, “We thought there would be a massive uprising against austerity and the Troika. But people seemed paralysed by fear – and chose to support the austerity measures.”

Indeed a leftist reaction to the Troika’s austerity measures never really took root in Portugal. And even though Bloco Esquerda gained supporters, the party remained far from influential. “My generation had either left the country or was too busy managing their life between social cuts and unemployment,” says Rivera, “And without the young generation, any radical politics will lose.”

Robles adds, “We don’t have a tradition of protest or radical policies like the Spanish, where everyone has grandparents that have served in the civil war… We don’t have any historic example for successful political intervention from below. It’s a rather slow process here.”

Still, both feel a change in the air since the geringonça proved stable and steered a new path away from austerity. But does that path also lead away from the EU? “In Bloco Esquerda we have different answers to these questions, depending on who you ask,” says Robles, “In the beginning, we were confident about a reform of EU towards more justice, democracy and solidarity among the member states. But now I think that we need to find completely new ways to cooperate in Europe.”

Outside Bloco Esquerda, Euroscepticism in Portugal is at a low with 54 percent of the population “tending to trust” the European Union, according to Eurobarometer (that’s a higher rating than Germany). Portugal is also making its government debt payments before deadlines, meaning there’s no confrontation on the horizon. And in that context, the anti-EU position of some Bloco Esquerda members seems off the mark.

But many young people in the cities aren’t happy about Portugal’s current economic boom. Even though unemployment is down, many of the new jobs are poorly paid and not secure. Investors have snapped up entire blocks in Lisbon and Porto and turned them into tourist apartments and hotels, making rents explode to an all-time high. Visit Lisbon’s old town during summer and “all you see is tourists photographing other tourists,” according to Rivera. “What they actually came here to see is slowly dying,” he says.

Vidal also considers herself a dying species. A noise-band is playing in her venue tonight, sending distorted feedback to the streets; “music to scare the wrong people away,” she calls it. Vidal and her daughter were forced out of their flat recently after an investor bought the building. She says Damas is also under threat, explaining investors have bought around the venue and she’s suddenly started receiving noise complaints. “It’s pretty clear they want to have us gone,” she says.

To Vidal the current boom is more of a curse. “We were the first well-educated generation after the end of the dictatorship. With the crisis we were entirely thrown to the garbage, unemployed and without hope. And now when people finally have jobs again, we can’t afford to live in the city because of the tourist hype. To me, that’s really not too much of an improvement,” she says.

I’m interested to know if she sees hope in the new faces of Bloco Esquerda. “I support their ideas,” she says, “But so far, I don’t feel too much of their influence.”

On the other side of the Iberian Peninsula, a visit to Barcelona hints at where Lisbon could be in a few years.

In a tiny square parallel to Las Ramblas lies the office of 36 year old woman Gala Pin Ferrando, part of the new municipal government responsible for the old-town district. Pin is a member of the citizen platform Barcelona en Comú, which managed to win the municipality just one year after its foundation.

Just like Podemos, Barcelona en Comú is a child of the anti-austerity protests in 2011 and 2012. Disappointed by the two major parties, activists occupying squares in Barcelona and Madrid developed a new basic democracy to continue initiatives and local groups even after the demonstrations ended.

“15M managed to direct the frustration of the people to a more constructive channel, asking who really was to blame for the whole mess,” says Pin. The blame lies with businessmen, bankers and corrupt politicians, according to Pin.

Just like the new mayor Ada Colau, Pin was active in the movement against evictions of people unable to pay their mortgages. “Negotiations with the banks and collecting signatures didn’t really help to bring forward our cause (so) we realized that we have to push into the institutions themselves,” she says.

Just a year before the election, Barcelona en Comú went public with a rough manifesto. After collecting 30,000 signatures for their manifesto to test its relevance among Barcelona’s citizens, they started negotiating with other parties and initiatives. Barcelona en Comú now unites many different initiatives, parties and individuals under a crowdsourced ethical code and key guidelines. “Our plan was to integrate as many voices as possible under the common cause to kind of reject the cliché of a torn up, segregated left,” Pin explains.

Pin describes the idea of a decentralized network of small assemblies working in different city-districts or specialising in certain topics like housing or architectural heritage.

The platform includes many players who wouldn’t describe themselves as leftist and Pin says that’s what makes Barcelona en Comú stand out from other left parties. “Of course our goals like social housing, regulated tourism and investment and the citizens’ right to public space derive from a left-leaning worldview, but in our way of organizing…we are far closer to people’s daily life,” she says.

The platform has huge plans, some of which are already enacted: no more new hotels in the old-town, car-free areas and fighting illegal Airbnb apartments. In the city hall, a corruption-mailbox has been installed, where any staff member can whistleblow suspicious behaviour.

But how do the older officials in the city hall feel about the sudden change of tone? In the first days of being in power, Pin realized how unwelcome she was; “With every gesture, every word, they seemed to be saying: ‘You’re not supposed to be here. You’re too young, too idealistic, too female.’” She tells a story of a public official kissing her forehead instead of shaking her hand during one of her first meetings.

But Pin is convinced that platforms like Barcelona en Comú can be a sustainable political model for Spain – and even Europe. “The 21st century will be the century of the cities,” she says, “We need to take control on the local level, where people’s problems are tangible.”

Does the EU play a role in her city-centric ideology? “I’m a big friend of the European idea, but I think we have to work on it,” she says, “My critique of the EU is pretty simple: I just wish for an institution that’s democratic and accountable to its citizens, that’s all.”

Pin’s utopia for Europe is a network of so called rebel-cities, governed by platforms like hers, working together in a network of shared principles. In other Spanish cities like Madrid, Zaragoza and Santiago, similar platforms have already put mayors in city halls.

A few kilometres north from Barcelona in the district of Grácia, 36 year old Cristian Subira, DJ and owner of non-commercial radio station dublab.es, has a darker prognosis for the new government. “In four, eight years at most, (Mayor) Ada Colau and Barcelona en Comú will be politically dead,” he says.

Sabira doubts the platform will be able to fulfil its constituents’ expectations. “I do support the platform’s principles approach and all, but I’m pretty sure that the move into institutions was far too early and too rushed,” he tells me while shutting down the studio equipment in his tiny studio. “These people, who have ruled the city for decades won’t just grab their belongings and be like, ‘Ok, you may take over now. Good luck!’ They will do everything to block any change for as long as they can,” he says.

Subira also feels left out personally, just like his culture-colleague Alexandra Vidal in Lisbon. He sees Barcelona’s subculture declining under a rising, tourist-friendly mainstream and he doesn’t feel any support from the new government. So far, he says, only projects and artists connected to the platform’s members have been supported with cultural funding. “That’s the old amigismo – doing something for your friends. It’s part of our nature here, but I was expecting more integrity from a government publicly condemning corruption,” he says.

Outside the studio, Subira tells me he hasn’t lost all hope for Barcelona en Comú yet. He tells me about a friends’ theatre project, where the audience had to guess the number of beans in a glass before every show. “Some said 20, others 2000 and both were called stupid by each other,” he says. After five shows, the guesses were averaged out. The result was close to the real number. “And for that solution,” Subira says, “every voice was necessary; the 20 and the 2000. I like that way of decision-making. And if Barcelona en Comú sticks to its principles, we can prove to the rest of the world that this method also works in politics… And if everything fails we can still say that we tried.”

Just like in Lisbon, nobody I spoke to in Spain had heard the ‘Pulse of Europe.’ But not many Germans seem to know about the geringonça in Portugal or Spain’s rebel cities. At least for this year’s elections, alternative approaches to politics in Germany seem to only come from the far-right; anti-EU, xenophobic alternatives that look for solutions in the past. Leaving the comfort zone of the status quo to challenge those narratives seems more than necessary. And even if the perfect utopia in Spain and Portugal is yet to be developed, there is definitely nothing wrong in trying.