Young and devoted

Where does this story begin? In a church or a mosque? During war or peace? In a school toilet or a punk concert? In Yugoslavia or what’s left of it?

Dragan, Vedran and Emir were all born after the dissolution of Yugoslavia in 1992. Dragan, 20 years old, is Serbian and Orthodox Christian. Vedran, 21 years old, is Croatian and Catholic. And Emir, 21 years old, is Bosnian and Muslim.

These three have never known one nation of Yugoslavia. But for many who are just a few years older, it seems like yesterday they lived in a single, stable country and today they woke to three relatively poor ones, burdened with a brain drain, public debt and still devastated by the war that killed 130,000 during the 1990s. Research from 2015 put the ‘triangle of bigotry’ in the countries that make up former Yugoslavia at around 15 percent: this means 15 percent of Serbs would not want a Croat or a Bosnian living next door; 15 percent of Bosnians would not welcome a Serb or a Croat as their neighbour, and 15 percent of Croats would not want a Serb or a Bosnian living in the adjacent flat. Those fifteen percent are often supported by their respective religious heads.

In former Yugoslavia, atheism went hand in hand with communism. But when Yugoslavia’s successor states bloomed, religion boomed. Religion became a tool to awaken national consciousness, emphasizing one of the few measurable difference between the three new nations, which are linked by language, culture and history. And so it is, that even now in these secular states, religion plays a lead role in politics. Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic consulted the Serbian Orthodox Church when forming his government. In Croatia, President Kolinda Grabar Kitarovic invited a respected Catholic friar from Zagreb to sanctify her office when she took the post. And Bosnia and Herzegovina President Bakir Izetbegovic says one is not a proper Bosnian unless they go to mosque.

Dragan’s story begins in a school toilet. Just in time to start fifth grade, Dragan moved from a small town in northeastern Serbia to the country’s second largest city, Novi Sad, and became the new kid at school.

“Two boys beat me every day… I tried to defend myself but it was useless. I was small, tiny,” he remembers, “Once, during a break, I ran away to the toilet and started crying. It was in 2008 when the Albanians took away Kosovo, when all that shit started happening, and I remember there were stickers everywhere, saying ‘Kosovo is the heart of Serbia’ and beneath, ‘The cross is the might and glory, the cross of Christ shall save us.’ One such sticker was on the door of the toilet. I was crying and looking at that sticker, and the tears were suddenly gone. Even though my parents are not very religious, I understood at that moment that I could rely on God, no matter how difficult things were.”

“I am not saying I decided then and there to become a priest – I don’t know that for sure even now – but I decided to embrace the hand of the Lord, which is always extended when we feel hopeless,” he tells me.

Let’s rewind a moment, to right there when Dragan said he still isn’t sure that he’ll join the clergy. Why is that?

“Because the Serbian Orthodox Church has its rules, which… how to explain this? There is little concession there,” he says, “A week ago, I received a lower grade on an exam because the professor did not like the way I was thinking. He said I took too much liberty. Do you understand the problem?”

Emir started his Islamic studies in Sarajevo two years ago. He grew up in Novi Pazar, a predominantly Muslim city in South-East Serbia – an area the Serbs call Raska and the Bosnians call Sandzak. Unlike Dragan, Emir comes from a religious family and since childhood he joined his father and grandfather at Lejlek Mosque, the oldest mosque in Novi Pazar. I wondered why he chose to study at the faculty in Sarajevo, when there is a similar one in his hometown.

“I don’t know… There are more people, more girls.” He laughs, takes a sip of soda and turns serious again, “I believe it is a special challenge to leave one’s home and go to a big city, into another country, into an entirely different environment. It wasn’t easy at all at first, but I knew I could not let myself down, or my family, or dear Allah in the first place.”

Emir talks with his parents every day, but he doesn’t tell them about the challenges he faces. “It is a matter of dignity for a man, to not burden others with his troubles. One week I had only 15 Markas (€7.50) in my pocket. What can a man do with them? He can spend them in Sarajevo in an instant. I bought only bread the first two days and I prayed… on the third day two students came to my door, wanting me to help them with Arabic. I wasn’t going to charge them, but they repaid me; they brought a jar of homemade jam, juice, a kilo of bananas… Can you believe it?,” he asks, “That is how God’s providence follows us even when we are unaware of it.”

God’s providence follows Vedran as well, even when he’s playing guitar in his punk bank. Vedran says most of his audience doesn’t know they’re watching an aspiring Catholic priest on stage but, he says “it would probably be good advertisement.”

Vedran’s band seldom performs – “Faculty comes first,” he says – but it is inspired by the late-sixties rock band “Zeteoci” (“The Harvesters”). The Harvesters was formed by students of theology from Zagreb, after the Second Vatican Council tried to improve relations between the Church and modern society.

I spoke with Vedran about how well the Church has kept up with modern society since The Harvesters heyday. I asked him whether he’d consider holding Mass via Skype, “Why not?” he says, “I am very open regarding this matter, and so are the colleagues I hang out with. I believe that the house of the Lord is all around us, not just in church. If Skype is a method of us becoming closer to our believers, achieving better communication, I am completely for it.”

Vedran say his attitude isn’t necessarily shared by his teachers. He tells me, “I suppose the majority would be highly reserved. However, times are changing. If someone had told us ten or twenty years ago that the Pope would advocate the rights of the LGBT community, or that he would admit being often sinful himself, many would have seen this ‘prophet’ as a crazy person.”

The Western Balkans is filled with contradictions; it is Western and Eastern, traditional and liberal, nationalistic and cosmopolitan. I wondered what extra contradictions these three young men must balance. They have chosen lives of tradition in a modern society; of holding religious texts instead of iPhones; of self-improvement through prayer, rather than filters and photoshop.

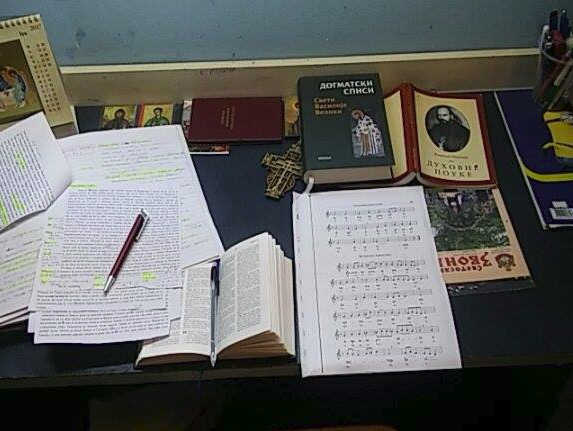

I asked each of them to photograph their desk from birds-eye view. Of course, there lies the Bible and the Koran. But also a yo-yo, a laptop, a can of Coca-Cola, a boomerang, a pack of condoms, a copy of ‘Lord of the Rings,’ an energy drink, and guitar chords.

In Serbia, 530 students enroll in bachelor theology studies each year, 485 students in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and 230 students in Croatia. Curious if Dragan, Vedran and Emir were a picture of the average student, I used Facebook to ask 20 students of Orthodox theology and as many from Islamic and Catholic faculties, to fill in a short questionnaire.

Out of 60 participants, 53 said they have friends of other religions, and 43 have atheist friends; 51 want to actively participate in interreligious dialogue for reconciliation in the Western Balkans; 57 want to learn as much as possible about other religions; 28 would like to introduce technological innovations into religious services; 52 are against nationalism; and 38 consider homophobia harmful.

The sample size is small but it shows support for views that are not necessarily endorsed by religious leaders in the Western Balkans. Will these students introduce new views to as they continue their religious careers? Can these religious institutions ever be used to reconcile rather than divide the Western Balkans?

“I would like for the Catholic Church to start spreading the sincere policy of peace and love,” Vedran tells me, “I totally like this style, but I am not sure this is its current official direction. The Church often needs someone who will symbolize the devil on Earth.”

Emir is more optimistic, and says the church “will be better.”

Dragan is silent for some time then asks, “Have you ever read Andric’s Letter from 1920? Until Andric’s clocks are harmonized, I don’t think there will be peace in the Balkans. Although it would sometimes be wiser for us to listen to our hearts instead of church bells,” Then he adds, “Is the last thing pathetic? If it is, cut it. But I, brother, really believe it.”

LETTER FROM 1920 By Ivo Andrić

Whoever lies awake at night in Sarajevo hears the voices of the Sarajevo night. Heavy and surely does the clock on the Catholic cathedral strike: two hours past midnight. More than a minute passes (exactly 75 seconds – I counted), and only then does the clock from the Orthodox Church resound with a slightly weaker, but piercing sound, and it strikes its two hours past midnight. A little after it, with a rasp, far-away voice, the clocktower of the Bey’s Mosque strikes 11 hours, Turkish hours, according to the strange calculations of distant, foreign corners of the world! The Jews have no clock to sound their hour, so God alone knows what time it is for them.

Thus at night, while everyone is sleeping, division keeps vigil in the counting of the late, small hours, and separates these sleeping people who when awake, rejoice and mourn, feast and fast by four different and antagonistic calendars, and send all their prayers and wishes to one heaven in four different ecclesiastical languages. And this difference, sometimes visible and open, sometimes invisible and hidden, is always similar to hatred, and often completely identical with it.